Dear Friends,

Greetings from the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

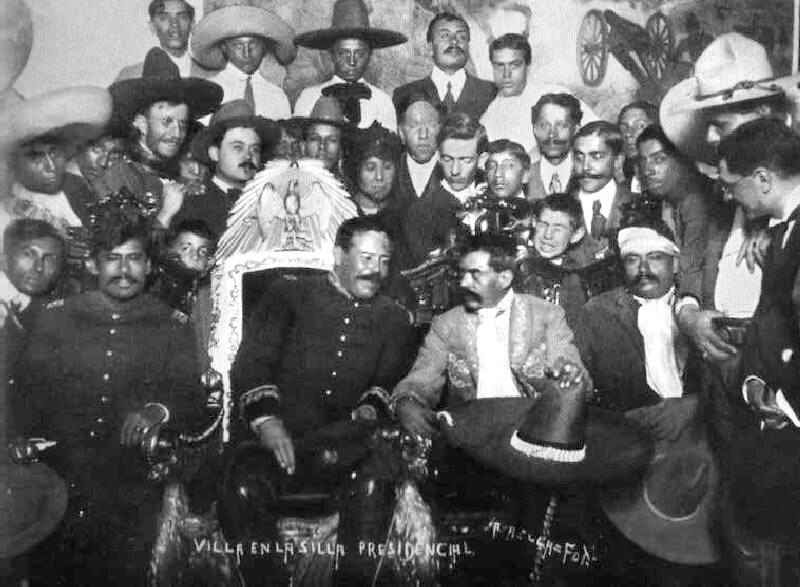

In December 1914, the two great leaders of the Mexican Revolution – Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata arrive at the National Palace in Mexico City. They are confronted by the golden presidential chair. Zapata sneers at it. ‘We ought to burn it down’, he says. ‘When a good man sits here, he turns bad’. Villa sits on it for Augustín Victor Casasola’s iconic photograph (above). Both Villa and Zapata return to their villages. Neither have the stomach for the city and the strong arm of order. ‘This village is too big for us’, Villa says. They are both assassinated.

The story of Villa and Zapata at the National Palace often comes to me these days. Zapata and Villa could not tolerate the corruptions of power. They wanted their revolution to honour the sacrifices of their fellow fighters and to be a balm against suffering. But, the powerful – the aristocrats and the oligarchs – sniffed at the margins. They would not relinquish power easily. Nothing shames the powerful, nor does guilt build up like bile inside their chests. Too much is at stake for them.

Force comes easily to the powerful. The United States has 883 military bases in 183 countries. Its tentacles strangle the planet (for more on this, see my report here). There will soon be a Fort Trump in Poland. It will move US-NATO’s military footprint closer to the Russian border. Threats will fly. Tensions will increase. Any attempt to dismantle the massive US military footprint will be set aside. A new governor has been elected in Okinawa (Japan). He is against the bases there, but the views of Governor Danny Tamaki and his constituents are irrelevant. Military force has a much more influential vote. A young girl from Okinawa, Rinko Sagara (age 14), reads out a poem in public that ends, ‘Now is our future’. She is of the heritage of Villa and Zapata. These are hopeful people. They are the opposite of the military base.

‘If you have a hammer, then everything looks like a nail’ – said a CIA operative to me a decade ago. The US military infrastructure gives its political leadership the delusion that all problems can be solved by military power. Diplomacy becomes marginal. The US hammer comes down hard on nails from one end of Asia to the other end of the Americas.

Everyone knows that Iran has no nuclear weapons policy. It was made clear in October 2003 when Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei condemned weapons of mass destruction. The International Atomic Energy Agency’s latest statement – as I show here – says that Iran has not violated the 2015 nuclear agreement. The main sentence needs no interpretation: ‘Iran is implementing its nuclear-related commitments under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action’. It is why the International Court of Justice ruled this week on behalf of Iran. The US sanctions on Iran, which will intensify on 5 November, are illegal. Trump’s administration puffed out its chest, stomped its feet on the ground and tore up the US-Iran Treaty of Amity (1955). All of this is based on deceit and all of it puts inhumane pressure on the 82 million Iranian people. War is threatened, because war is a habit.

So are sanctions, so are threats. Trump has forced Canada and Mexico into a new trade deal. Scott Sinclair of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternativestells us that this deal is ‘just another corporate-driven trade deal. It extends monopoly protection for Big Pharma, so Canadians and Mexicans end up paying more for medicines….Perhaps the best thing that can be said about [the new deal] is that Trump’s bark was worse than his bite’. But, even that is to be seen. Earlier this year, a group of Mexican intellectuals put together a bookabout the US-Canadian-Mexican trade deal, which anticipated what was going to come. More than half of the Mexican population was not born when NAFTA was signed in 1994. They do not want Mexico to be forced into a position of subordination. Nor do the Canadians.

‘This village is too big for us’, said Pancho Villa. He meant its attitudes. It was not willing to tolerate human emotions such as mutual regard and mutual aid. UN Habitat estimates that by 2050 the world’s urban population will increase to 6.4 billion – with 95% of that growth taking place in the cities and towns of Africa, Asia and Latin America. Already a billion human beings live in slums. It is estimated that by 2030, the world slum population will increase to 3 billion.

Nothing about life in a slum should be whitewashed. Shack dwellers – as the people who live in slums in South Africa call themselves – do not stray from a consistent fight against the conditions of their lives. They would like better housing, cleaner streets, healthy air, drinkable water, playgrounds for their children, community centres for their elderly. But, those who killed Villa and Zapata and those who build military bases around the world do not share in these dreams.

That is why the militants of Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM) – South Africa’s shack dwellers’ organisation – are being killed off, one by one. The list of those killed is long – from Nkululeko Gwala (2013) to S’fiso Ngcobo (2018), from the death of Jayden Khoza (two weeks old) in a violent attack on the shacks to the murder of Inkosi Thulani Mjanyelwa (the chief of Mpondoland). The most precious target for the killers is S’bu Zikode, the leader of AbM, now underground. ‘I cannot accept this as the end of my political life’, Zikode told me recently. ‘If this is a political assassination of my political life, then I’m not prepared to back down’. He is a brave man. At New Frame, Zandile Bangani talks to Zikode’s wife Sindi Mkhize, who says, ‘The life we are living is not nice’. There is trouble every day. But, she – like Zikode – is firm. ‘We will work for the people until their demands are met’.

It is impossible not to see Palestine’s villages and towns on the West Bank as rural and urban slums, the conditions of their improvement stolen by the Israeli occupation. Violence is a normal situation, as is the degradation of the environment where the Palestinians struggle to live lives of dignity. Most recently, in Khan al-Ahmar, the Israeli settler colonialists have been pouringsewage into the water used by the Palestinians, who hold on to their meagre lands against all odds. The Israeli authority has threatened to demolish this village, but the Palestinians have gathered here to defend their rights to the land. Jamal Juma of Stop the Wall has been documenting the struggle each day.

People like S’bu Zikode, Sindi Mkhize and Jamal Juma are our Villas and Zapatas. They do not carry the gun. But they are people who are not seduced by power.

This Sunday, the people of Brazil will go to the polls. Jair Bolsonaro, a near fascist, leads the polls to become the next president of Brazil. Nearly half of the Brazilian people dislike him intensely. His support for the military dictatorship (1964-1985) disgusts many, as do his horrible comments about women, gays and Afro-Brazilians. This is an unpleasant man. Which is why the march of mostly women across Brazil came with a simple hashtag – Not Him (#EleNão). Anyone but Bolsonaro is the resounding cry (for an explainer on the election, see my article in New Frame). The Brazilian people’s favoured candidate – Lula – is in prison. He has asked them to transfer their support to Fernando Haddad and Manuela D’Ávila who are the presidential and vice-presidential candidates of Lula’s Workers’ Party. It is likely that no-one will win more than 50% of the vote on 7 October, and that the top two candidates will fight it out in the second round on 28 October. It will, then, be a fight between Bolsonaro and Haddad. Not Him. That’s the phrase. But more than that, it is also for Haddad a defence of the humane policies of the Workers’ Party government that ran from 2003 to 2016. It was that government that almost ended hunger in Brazil. This week, UN Secretary General António Guterres said, ‘Poverty is not inevitable’, referring to the UN goal to end poverty by 2030. A vote for Bolsonaro will certainly not lead in that direction. A vote for Haddad might.

For background on this election, please read our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Dossier no. 5, Lula and the Battle for Democracy (June 2018). For up to the minute coverage on the Brazilian election, go to Brasil de Fato.

Fifty years ago this week, in Mexico City, the state forces attacked a student protest at the Plaza of Three Cultures. Hundreds of people were massacred there. A few weeks later, Mexico City hosted the Olympic games, where two US athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos lifted their fists in a powerful salute. Smith, Carlos and the Australian athlete Peter Norman had won medals for the 200m race. All three wore human rights medals.

Our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research designer Tings Chak has written an important and delightful essay about the designs for the Olympics, the protests in Mexico, the massacre at the Plaza and the counter-designs by the protestors (see above for one example). It ends with a lovely hymn by Violeta Parra,

Long live the students,

gardens of joy!

They are birds that don’t frighten

because of animals nor police,

not scared of bullets

nor packs of barking dogs.

For this week’s image, Tings has drawn the Mexican journalist and editor Elena Poniatowska, the founder of La Jornada – one of Mexico’s best newspapers – and the author of La Noche de Tlatelolco (1971), one of the best books on the massacre of the students. The book opens with the students – like the troops of Zapata and Villa – walking into the square. ‘They are many. They come on foot. They come laughing…Carefree young people who do not know that tomorrow, within two days, within four, they would be lying still, their lifeless bodies swelling under the rain’.

Warmly, Vijay.

PS: Coming up on Tuesday, October 9, Dossier no. 9 on the Kerala floods with an original drawing by Orijit Sen on the cover. Find it at our website.